ON THE FORGETTING OF CORPORATE IRRESPONSIBILITY

SÉBASTIEN MENA City University London

JUKKA RINTAMÄKI Aalto University

PETER FLEMING ANDRÉ SPICER City University London

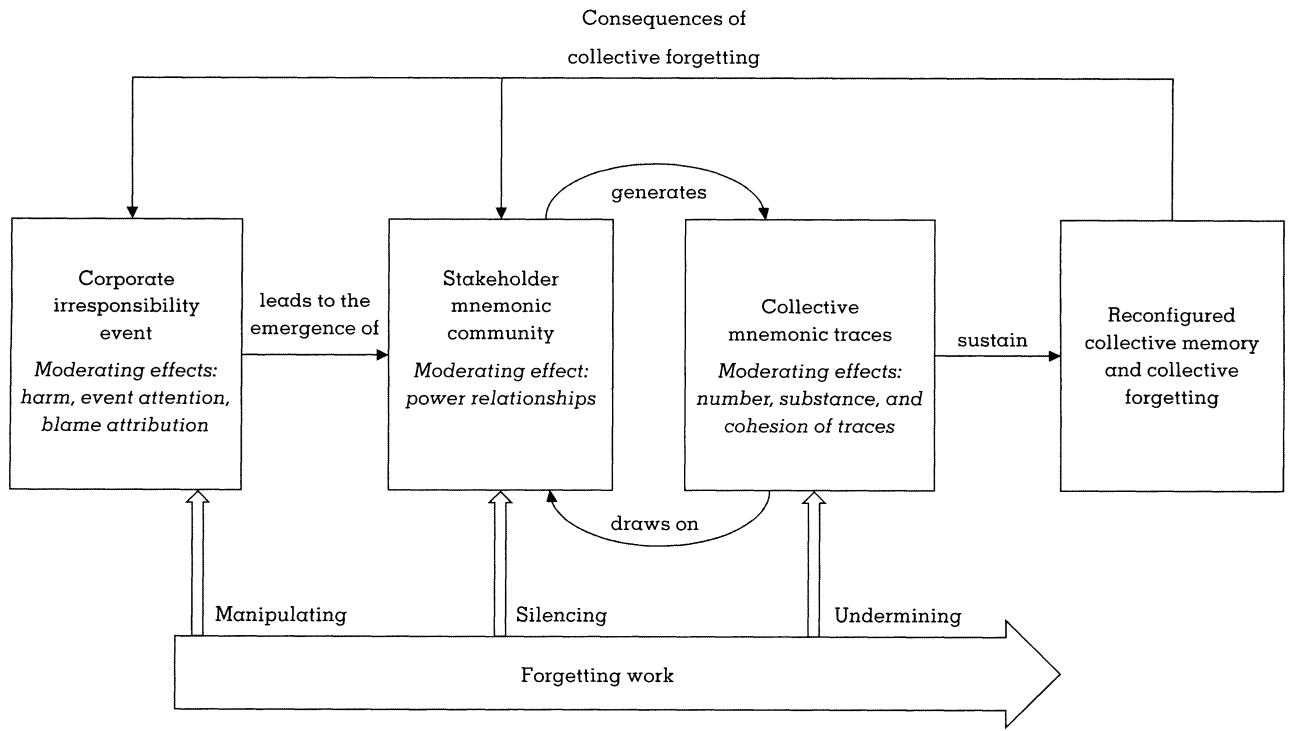

Why are some serious cases of corporate irresponsibility collectively forgotten? Drawing on social memory studies, we examine how this collective forgetting process can occur. We propose that a major instance of corporate irresponsibility leads to the emergence of a stakeholder mnemonic community that shares a common recollection of the past incident. This community generates and then draws on mnemonic traces to sustain a collective memory of the past event over time. In addition to the natural entropic tendency to forget, collective memory is also undermined by instrumental “forgetting work,” which we conceptualize in this article. Forgetting work involves manipulating short-term conditions of the event, silencing vocal “rememberers,” and undermining collective mnemonic traces that sustain a version of the past. This process can result in a reconfigured collective memory and collective forgetting of corporate irresponsibility events. Collective forgetting can have positive and negative consequences for the firm, stakeholders, and society.

Some instances of corporate irresponsibility, such as Nestlé’s marketing of baby formula in developing countries, Nike’s use of child labor, and Enron’s fraudulent accounting practices, remain at the forefront of our collective memory. Other instances, however, have largely been forgotten. Take the example of HealthSouth, one of the largest and most well-respected rehabilitation hospitals in the United States. In 2003 the firm was embroiled in a serious and widely publicized accounting scandal when then CEO, Richard Scrushy, was accused of inflating profits by U.S. $$ 1.4$ billion. At the time, many considered the firm to be a lost cause as it approached bankruptcy. Today, however, its past woes seem to have almost been forgotten. The organization renewed its focus on its core capabilities, relisted on the stock exchange, and completely rebuilt its reputation (Goodman, 2003).

The process of forgetting HealthSouth’s irresponsible past appears to have been actively managed, at least in part. After Scrushy departed, and “as part of its effort to rebuild the brand’s credibility, the new management removed all traces of Scrushy from corporate headquarters and the company website” (Goodman, 2003). Scrushy’s name and his corporate message were erased from the conference center at HealthSouth headquarters. The company store and museum were closed, and the executive offices were opened to all employees who previously had been barred from this area under Scrushy (Goodman, 2003). This example indicates that while acts of corporate irresponsibility can be “naturally” forgotten over time, forgetting can also result from active and instrumental work. In this article we conceptualize this instrumental work and how it might facilitate the collective forgetting of corporate irresponsibility events.

Corporate irresponsibility events are temporally defined organizational actions that cause harm to stakeholders. Current research has focused primarily on the question of how organizations and their stakeholders react to such traumatic events in the short term (e.g., Barnett,

2014; Bundy, Shropshire, & Buchholtz, 2013; Godfrey, Merrill, & Hansen, 2009; Rowley & Moldoveanu, 2003). We know less about how corporate irresponsibility events can be collectively forgotten over longer periods of time. Some researchers have addressed forgetting in and around organizations. Investigations of organizational learning and memory (Levitt & March 1988; Walsh & Ungson, 1991) show that organizational knowledge can be forgotten (e.g., Brunsson, 2009; de Holan & Phillips, 2004; Fernandez & Sune, 2009; Hedberg, 1981). There is also a social constructionist approach to memory in organizations (see, for example,Booth & Rowlinson, 2006; Coraiola,Foster, & Suddaby, 2015; Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Rowlinson, Booth, Clark, Delahaye, & Procter, 2010; Rowlinson, Hassard, & Decker, 2014; Üsdiken & Kieser, 2004) in which researchers examine how organizations strategically manage the past for present ends and, in the process, forget certain past events (e.g., Anteby & Molnár, 2012; Foster, Suddaby, Minkus, & Wiebe, 201l; Suddaby, Foster, & Trank, 2010). This research, however, focuses in large part on intraorganizational mnemonic processes. In the few studies of remembering and forgetting at a supraorganizational level, researchers have devoted attention to mnemonic interactions between competitors (e.g., Greve, 2005; Madsen, 2009). As this article will demonstrate, however, the collective forgetting of corporate irresponsibility involves other significant stakeholders, including employees, consumers, civil society organizations, the state, or the media. To understand this process, we require a model that accounts for remembering and forgetting on the part of internal and external stakeholders. This is critical because wider stakeholder groups play a vital role in holding firms accountable for past corporate irresponsibility events and ultimately improving their social performance (Lange & Washburn, 2012).

To better explain how a corporate irresponsibility event can be forgotten by a community of stakeholders, we turn to social memory studies (for a review see Olick & Robbins, 1998). Specifically, we build on the concept of collective memory-the ways a community may perceive and reconstruct the past to meet its present needs (Halbwachs, 1992). Although our context is admittedly unique, since “disasters are inherently memorable” (Madsen, 2009: 873), many instances of corporate irresponsibility are nevertheless forgotten (e.g., Cooke, 2003; Crane, 2013; Fig, 2005).

Social memory studies are useful in this regard. They acknowledge that collective forgetting may result from natural inertia, but they highlight the fact that it can also be hastened by the instrumental activity of interested actors (Fine, 2012; Olick, 2007; Schudson, 1995). By developing this insight, we argue that “forgetting work” is undertaken by actors with an interest in the collective forgetting of a past corporate irresponsibility event.

We propose that forgetting work unfolds over time. In the short term, actors can manipulate the initial collective memory of a serious incident—for example, by attempting to influence how the media report on it. In the longer run, actors can silence stakeholders, especially vocal ones who seek to sustain the remembrance of the event. Over time, firms can undermine the collective mnemonic traces of the past event—for instance, by fabricating or destroying evidence. When forgetting work is successful, the collective memory of the past event is reconfigured, eventually resulting in its collective forgetting. This may have positive organizational consequences, such as maintenance of the firm’s identity and legitimacy among stakeholders (Anteby & Molnár, 2012; Brown & Starkey, 2000), but also negative ones, such as failure to learn from past mistakes (Madsen, 2009) and the increased likelihood a similar event will happen again (Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 2011).

By positing this argument, we make several contributions to management and organization studies. First, we provide an account of corporate irresponsibility that extends beyond the immediate reactions to wrongdoing exhibited by firms and stakeholders (e.g., Barnett, 2014; Bonardi & Keim, 2005; Bundy et al., 2013; Waldron, Navis, & Fisher, 2013), since our article considers longer-term mnemonic processes. Second, given that social constructionist approaches tend to focus on the positive features of organizational memory and forgetting (e.g., Anteby & Molnár, 2012; Suddaby et al., 2010), we reveal a darker side of mnemonic processes in which past transgressions that ought to be remembered are forgotten (e.g., Booth, Clark, Delahaye, Procter, & Rowlinson, 2007). Third, we contribute to studies of organizational memory and learning (e.g., Darr, Argote, & Epple, 1995; Madsen, 2009) by drawing attention to the importance of a wider community of stakeholders engaged in mnemonic activity.

The article is structured as follows. We first review the organizational learning and memory literature before examining the contribution that social memory studies make to conceptualizing collective memory and forgetting. We then develop our model by discussing corporate irresponsibility events in relation to harm, attention, and blame attribution. We explain how mnemonic communities and traces emerge from such events. Following this, we focus on the notion of forgetting work and its consequences for collective memory. Finally, in the discussion section we posit various moderating effects, limitations, and avenues for future research in management and organization studies.

MEMORY AND FORGETTING

Organizational Learning and Memory

Memory has been studied for some time by organization and management scholars, especially in connection with knowledge management and organizational learning (Cyert & March 1963; Levitt & March 1988). Researchers have examined how organizations learn by doing in order to improve their production processes (Argote, 2012; Crossan, Lane, & White, 1999; Fiol & Lyles, 1985). They have found that organizations embed past knowledge in their organizational memory that is stored in and retrieved from “retention bins” (Walsh & Ungson, 199l). One of these retention bins is employees, who do the learning for their organization and encode it into other retention bins, such as the organization’s culture, routines, and structure (Argote & Miron-Spektor, 201l; March & Olsen, 1975; Walsh & Ungson, 1991). Top management can assist employees in encoding the knowledge they generate by facilitating communication and knowledge transfer (Crossan et al., 1999; Tsang & Zahra, 2008).

Relatively less attention has been paid to knowledge depreciation (e.g., Darr et al., 1995; Madsen, 2009), unlearning (e.g., Hedberg, 1981; Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984), and forgetting (e.g., de Holan & Phillips, 2004; Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 2011). Forgetfulness occurs when knowledge, even that which is embedded in organizational memory, is lost over time (Darr et al., 1995). This is typically due to employee turnover (Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 201l; Levitt & March 1988), loss or destruction of archival records, knowledge obsolescence (Argote, 2012), and organizational reform (Brunsson, 2009). This loss of knowledge may or may not be intentional (de Holan & Phillips, 2004).

When it is intentional, it is often assumed to be beneficial in terms of firm performance (Hedberg, 1981; Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984).

While the learning literature has advanced our understanding of mnemonic processes within organizations, it has offered less about supraorganizational collective forgetting. Other studies have examined forgetting beyond the boundaries of a single firm (e.g., Argote, Beckman, & Epple, 1990; Darr et al., 1995). Madsen (2009), for example, investigated how U.S. coal mining firms forget accidents involving other firms in the industry. He found that while large-scale mining disasters remain in the memory of the population of mining firms and to some extent prevent the occurrence of future accidents on other sites, smaller accidents are much more quickly forgotten. Similarly, Desai (20l4b) revealed how negative media coverage of U.S. railroad accidents at other railroad firms can concentrate organizational attention and facilitate the implementation of safety measures, whereas the lack of such additional information does not, thus leading tc a failure to learn from the mistakes of others.

The vast majority of this research on interorganizational learning focuses on efficiency and competitive dynamics within and between firms (Argote, 2012). As a result, it often does not consider memories held by stakeholders (such as civil society organizations, governments, or local communities) who are not competing firms. These other stakeholders matter because they can help to hold firms accountable for their activities (Lange & Washburn, 20l2). Indeed, some stakeholders can play a central role in maintaining memories of past traumatic events, reminding others of corporate wrongdoing and putting pressure on other firms not to make similar mistakes (Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith, & Taylor, 2008). To help us consider the role that these stakeholders play in mnemonic processes, we now turn to social memory studies.

Social Memory Studies

Social memory studies investigate the mnemonic processes we collectively use when remembering and forgetting. The central question addressed in this body of research concerns the way past events are socially reconstructed in light of current beliefs and norms to serve the present purposes of α community (Gross, 2000; Olick, 1999; Olick & Robbins, 1998). This emphasis is compatible with contemporary physiological and psychological research viewing memory as an active process of construction and reconstruction, rather than the mere storage and retrieval of information (Brockmeier, 2010; Olick, 2007; Schacter, 1995, 2002). Social memory studies bring to the fore the collective mnemonic practices of remembering and forgetting that keep a past event relevant. This allows us to analyze the way past events are remembered and also how they can be reinterpreted or forgotten by communities over time (Halbwachs, 1997/1950; Schwartz, 1982).

No doubt memories of a past event can and usually do vary between individuals. However, collective memories are not simply the aggregate sum of individual memories (Conway, 2003; Olick, 1999; Schudson, 1995). While the act of remembering is individual, actors often draw on shared narratives of a past event to frame and inform how and what they remember (Brockmeier, 2002; Conway, 2003; Halbwachs, 1997/1950; Olick & Robbins, 1998). In this sense, collective memories are shared, extraindividual representations of the past that resonate with members of a community at a certain point in time (Olick, 1999, 2007; Zerubavel, 1996).

Collective memories of a past event are socially sustained over time by mnemonic communities (Misztal, 2003; Zerubavel, 1996), which are groups of people and organizations that coalesce around a definite understanding of a past event (Aksu, 2009; Halbwachs, 1997/1950). While some people in a mnemonic community may have experienced the event directly, others may have learned about it only indirectly. For example, people of the Jewish faith have developed a mnemonic community around the shared remembrance of the Holocaust, even though many did not experience it firsthand (Hansen-Glucklich, 2014). While some members of a mnemonic community are relatively passive in the collective remembering or forgetting process, others are more active and influential. Active members have an interest in evoking and narrating a specific version of a past event for a variety of reasons (Fine, 2001; Lang & Lang, 1988). For example, Fine (1996) demonstrated how the U.S. presidency of Warren Harding is remembered as one of incompetency, despite some welldocumented successes. This memory was shaped by “reputational entrepreneurs,” who used a number of financial and moral scandals in Harding’s cabinet to besmirch the entire presidential term.

Some actors can therefore keep a past event salient in the collective memory of a community by linking narratives about the past with present interests and prerogatives (Olick, 2007; Schudson, 1995). Importantly, this does not mean that others, outside the community, cannot remember this event. Rather, certain memory processes can function to galvanize social interconnectivity within a community as members draw on narratives of the past to crystalize present objectives.

As a mnemonic community forms around a common representation of an event, it creates collective mnemonic traces of that event. A mnemonic trace is a reminder, like a ritualized story, that helps members of a community remember what the shared narrative of their past is (Halbwachs, 1994/ 1925; Spillman, 1998). These traces are drawn on by the mnemonic community to sustain the collective memory of a past event, but sometimes also to reconfigure or reframe it (Fine, 200l; Olick & Robbins, 1998). Biases and interpretations are inevitably built into mnemonic traces (Gross, 2000). They therefore carry symbolic meanings, which embody the beliefs and norms of a mnemonic community about a past event at a particular point in time (Halbwachs, 1997/1950; Schudson, 1995). Mnemonic traces of past events can also be “maintained by objects in the world” (Hirst & Manier, 2008: 186). Such “objectivized” (Assmann, 1995b: 128) traces may take the form of archival documents, monuments, or museums that publicly represent the past event (Halbwachs, 1997/1950; Nora, 1989; Ricoeur, 2004). Therefore, mnemonic communities may draw on immaterial (e.g., stories redolent with symbolic import) or material (e.g. statues or archives) traces, and often both. For example, an army regiment might collectively remember a particular battle by creating and drawing on material mnemonic traces like regiment regalia, photographs, or framed commemorations for outstanding duty. But immaterial traces will also be important, such as regular storytelling about events leading up to the battle or myths of bravery (Thornborrow & Brown, 2009).

Collective Memory and Forgetting

A mnemonic community can reconfigure its collective memory over time, modifying and discarding mnemonic traces in light of its present beliefs. When this occurs, some aspects of past events are remembered while others are forgotten (Assmann, 1995a; Schacter, 1995). As Schudson puts it, $" \mathtt { A }$ way of remembering is a way of forgetting" (1995: 348). This suggests that collective remembering and forgetting are not two processes working in diametrically opposed directions. Rather, they simultaneously create a shared version of the past to be used in the present. Collective memory, therefore, should be conceptualized as “a highly selective process which oscillates between remembering and forgetting” (Blaschke & Schoeneborn, 2006: 109).

Collective forgetting is defined in social memory studies as the “absence of institutionalized memory” (Fine, 2012: 59) or the nonexistence of a shared version of the past. When a specific collective memory is reconfigured, it can create several competing versions of a past event (Fine, 2001). It can also make a past event seem irrelevant to present matters. As a result, the past event is ultimately erased from collective memory and forgotten (Assmann, 1995a). Indeed, when a past event is not picked up and used as a template for future action, it ceases to remain in collective memory (Fine, 2012).

Memory typically fades over time both at the individual (Schacter, 2002) and collective (Schudson, 1995) levels. It is, in fact, forgetting, rather than remembering, that is the primary function of memory (Blaschke & Schoeneborn, 2006), given the vast number of events we encounter. Social memory studies suggest that passing time creates an emotional distance between a mnemonic community and past events. When this transpires, mnemonic communities are likely to forget about the past event (Erdelyi, 1990; Schacter, 1995, 2002; Schudson, 1995). Forgetting more than we remember is often useful. Selective forgetting can have positive consequences (Hedberg, 1981; Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984), since it helps mnemonic communities become sensitive to environmental changes and continue to evolve in response to their surroundings (Blaschke & Schoeneborn, 2006). Studies of organizational learning have similarly demonstrated that selective forgetting is crucial for sustained organizational life and continuity (Brown & Starkey, 2000; de Holan, 2011). For example, in a comparative study of several hotels in Cuba, de Holan and Phillips (2004) revealed the important role of managed organizational forgetting in the replacement of old routines with new and more efficient ones. Similarly, Anteby and Molnár (2012) examined how an aeronautics firm willfully omitted certain past events in its “rhetorical history” (Suddaby et al., 2010), in an effort to maintain its identity. Social memory studies also often view collective forgetting as positive, since it prevents cognitive overload and helps communities make peace with their past (Connerton, 2008; Erdelyi, 1990; Olick, 2007; Ricoeur, 2004).

While forgetting can result from relatively passive, inertial mnemonic forces, it can also entail more active, instrumental processes (Fine, 2001, 2012; Lang & Lang, 1988; Olick, 2007). This has been acknowledged in organizational learning, as Easterby-Smith and Lyles point out:

History . . . may be reinvented or rewritten to provide a rationale for current decisions and ambitions. The rewriting of history may be deliberate and conscious (unlearning), or it may be largely accidental and unconscious as a result of the comings and goings of powerful individuals and groups or simply due to people forgetting the past (2011: 313).

Hence, some members of a mnemonic community, with an interest in a specific version of the past, act with different levels of intentionality to reconfigure and reconstruct preceding events. In doing so they modify, downplay, or even erase these events from collective memory (Brockmeier, 2002; Kammen, 1995).

Building on this insight, we explore the activities that underpin the collective forgetting of corporate irresponsibility events in more depth. While we acknowledge that there are entropic forces that can drive the collective forgetting of such events, we argue that instrumental work may facilitate this forgetting process. We are particularly interested in understanding why some corporate irresponsibility events are forgotten more rapidly than others.

THE COLLECTIVE FORGETTING OF CORPORATE IRRESPONSIBILITY

In order to help conceptualize the collective forgetting of corporate irresponsibility events, we posit the following model, as illustrated in Figure l. To explain the model, we begin by examining the several important short-term conditions inherent in a corporate irresponsibility event: the degree of harm to stakeholders, the level of attention the event receives, and the attribution of blame. These conditions can lead to the formation of a mnemonic community that includes the focal firm as well as internal and external stakeholders. The resulting stakeholder mnemonic community both generates and draws on mnemonic traces to remember and forget some aspects of the past event. Using these mnemonic traces, members of the community negotiate a shared memory of the event that can change over time.

This collective memory can also be shaped by forgetting work, which can include manipulating the short-term conditions of the event, silencing specific stakeholders, and undermining mnemonic traces. When forgetting work is successful, it reconfigures the collective memory of a past corporate irresponsibility event. As we explain below, this makes it more likely that the mnemonic community will forget the event. This can have positive consequences, such as identity maintenance, as well as negative consequences, such as failure to learn from past mistakes.

Corporate Irresponsibility Events

Corporate irresponsibility involves a firm doing harm to its environment, intentionally or not (Campbell, 2007; Minor & Morgan, 2011; Scherer & Palazzo, 2007). A corporate irresponsibility event is a temporally compact sequence of activities (Hoffman & Ocasio, 200l; Nigam & Ocasio, 2010) that a firm is closely associated with. These activities generate significant negative consequences for stakeholders and therefore endanger the firm’s legitimacy and can lead to further negative outcomes for the firm, including fines or bankruptcy (Fleming & Jones, 2013; Godfrey et al., 2009; Lin-Hi & Müller, 2013).

In general, scholars tend to examine three important short-term conditions of a corporate irresponsibility event that influence the initial collective memory of the event: (1) the harm the event creates, (2) the attention given to the event, and (3) how blame is attributed (Shrivastava, Mitroff, Miller, & Miclani, 1988). Corporate irresponsibility events inflict varying degrees of harm on several internal and external stakeholders (Barnett, 2014; Schrempf-Stirling, Palazzo, & Phillips, 2016). The most obvious harm is the loss of human life. But corporate irresponsibility events can generate more widespread harm having an impact on a range of stakeholders, such as the loss of nonhuman life and the loss of livelihoods in local communities. The diversity and complexity of the harm created by an event can generate significant uncertainty among stakeholders (Perrow, 1984; Shrivastava et al., 1988). One way uncertainty can be reduced is by means of event attention.

FIGURE 1 Collective Forgetting of Corporate Irresponsibility

Corporate irresponsibility events attract different levels of attention (Desai, 2014b; Hoffman, 1999; Nigam & Ocasio, 2010). The more focused the attention of stakeholders, the more likely the event will generate stakeholder responses (Barnett, 2014; Hoffman & Ocasio, 2001; Ingram, Yue, & Rao, 2010) and the more salient the event will be for affected stakeholders and the general public (Desai, 2014b). The media play a key role in the short-term struggle over whether an event holds our attention (e.g., Holt & Barkemeyer, 2012; Zavyalova, Pfarrer, Reger, & Shapiro, 2012). Being largely focused on an immediate time horizon (Barkemeyer, Holt, Figge, & Napolitano, 2010; Kleinnijenhuis, Schultz, Utz, & Oegema, 2015), the media affect the collective memory of a corporate irresponsibility event in the short period of time directly following the event. The media debate that follows a corporate irresponsibility event, for example, frames it in a variety of ways that are usually driven by the way blame is attributed to different actors (Hoffman & Jennings, 2011).

Stakeholders seek to reduce uncertainty by assigning responsibility and attributing blame for the event to particular actors (Lange & Washburn, 2012; Pfarrer et al., 2008). This social process of sensemaking involves retrospective inquiry into what transpired during an event, who the central decision makers were, and who may be ultimately culpable for the event (Gephart, 1993). This process may occur in a range of different institutionalized forums, such as public inquiries (Hilgartner & Bosk, 1988), the media (Desai, 2014b; Zavyalova et al., 2012), and direct firm-stakeholder confrontations (Waldron et al., 20l3). Through blame attribution, the complexity and overlapping responsibilities associated with the event are reduced and projected onto identifiable actors (Gephart, 1993), even if such attribution can be disrupted (Javeline, 2003).

of blame, it often triggers the development of a mnemonic community. The mnemonic community generated by these processes can include the firm and some of its internal and external stakeholders, like the firm’s members (managers, employees, shareholders, etc.), competitors and business partners, consumers, the media and journalists (who provide accounts of the event), governments and regulatory institutions, and other relevant civil society members that may be affected (e.g., the families of employees, local communities, etc.) or may have an interest in the event (e.g., NGOs or activists). A stakeholder mnemonic community is likely to undergo changes in membership over time. This occurs when external actors are attracted to the community by renewed interest in the event or when others join because they are affected by delayed externalities of the event. Hence, a stakeholder may be part of a mnemonic community without having directly experienced the event in question (Zerubavel, 1996). Typically, employees not directly involved in causing the event or not experiencing its direct consequences will hear about it from management, fellow employees, customers, and, perhaps the media (Desai, 2014b; March & Olsen, 1975).

Within a mnemonic community, some members “compete to control collective memory, and this is subject to dynamic change over time” (Fine, 2012: 94). Most members of these communities are relatively passive when it comes to asserting the 295). However, other members—whom we will call “rememberers”—engage more actively in shaping how the event is remembered. Rememberers often have an interest in institutionalizing a certain version of the event. Activist groups frequently play the role of rememberers for past corporate irresponsibility events. However, they often lack the necessary resources and coordination mechanisms to sustain their campaigns over long periods of time (Taylor, 1989). Moreover, the most vocal rememberers are likely to change as time passes because of the resources they can access and their ability to sustain interest in the cause (Pfarrer et al., 2008).

Stakeholder Mnemonic Community

When a corporate irresponsibility event occurs causing significant harm, attracting sufficient attention, and provoking specific attributions

Collective Mnemonic Traces of Corporate Irresponsibility Events

A stakeholder mnemonic community generates a range of collective mnemonic traces of a corporate irresponsibility event. The community also draws on these traces to sustain its collective memory of the event. Stakeholders often create highly symbolic mnemonic traces, such as commemorations of workers killed or stories of how tragic events unfolded (Hobsbawm & Ranger, 1983). Employees can generate narratives about their firm’s past, and management can highlight certain aspects of an event while obscuring others (Booth et al., 2007; March & Olsen, 1975). Collective mnemonic traces of corporate irresponsibility events can also have a material component, like the ruins of a collapsed factory, traces of pollutants in the natural environment, or the physical deformities they may cause (Shrivastava et al., 1988). Firms often produce a variety of documents about the event, including internal memos and public statements that proffer particular narratives of the event. Other stakeholders, NGOs and the media in particular, also generate written traces in the form of incriminating reports on the firm’s activities or journalistic analyses. Such collective mnemonic traces provide the raw material that mnemonic communities use to help sustain the collective memory of the event and, in doing so, maintain a particular version of the past.

FORGETTING WORK

Collective memory is affected by instrumental forgetting work (Fine, 2012), even if it is “not necessarily calculated” (Schudson, 1995: 352) and the outcomes are not always those that were expected (Olick & Robbins, 1998). Forgetting work involves purposeful attempts to reconfigure, dilute, and thwart the collective memory of an event. We propose that this occurs through the articulation of narratives (Booth et al., 2007; Brockmeier, 2002) and the exercise of power (Kammen, 1995; Ricoeur, 2004; Schudson, 1995). Narratives give meaning to the past event so that some aspects are attended to while others are obscured and disregarded (Booth et al., 2007; Brockmeier, 2002; Ricoeur, 2004). Exercise of power “can shape the interactions among actors that are the underpinnings of memory structures” (Casey & Olivera, 201l: 308). Power can sanction some stakeholders as the legitimate bearers of collective memory while disempowering or disqualifying others (Brockmeier, 2002; Ricoeur, 2004; Zerubavel, 1996).

Forgetting work can be undertaken by firms, their management, or other actors (such as industry associations and sometimes employees)

who have an interest in mitigating the short- and long-term negative impacts of the event and enhancing the positive consequences of forgetting. Forgetting work does not necessarily imply coordinated and intentional action. Rather, it is often the result of a range of activities with different intended time horizons and degrees of intentionality. Furthermore, forgetting work rarely exists in isolation. Firms engaged in forgetting work can also react to an event in other ways at the same time, like asking for forgiveness (Pfarrer et al., 2008).

We suggest that forgetting work unfolds over time. In the short term it involves manipulating the immediate perceptions of a corporate irresponsibility event. In the longer term forgetting work can entail silencing members of the mnemonic community and undermining collective mnemonic traces. We now examine these three different types of forgetting work in more depth.

Manipulating: Forgetting Work Following α Corporate Irresponsibility Event

Manipulation is the primary form of forgetting work that immediately follows an instance of corporate irresponsibility. Its purpose is to control the initial collective memory of an event so that the negative association between the firm and the event will be diminished. Impression management studies demonstrate how, following (and sometimes prior to) organizational failures, errors, or scandals, organizations attempt to influence stakeholder perceptions (Elsbach, Sutton, & Principe, 1998; McDonnell & King, 2013). This strategy is directed at both internal (e.g., employees) and external (e.g., journalists, NGOs) stakeholders (Bansal & Clelland, 2004; Desai, 2014a; Elsbach et al., 1998). In a similar vein, forgetting work conducted via manipulation is aimed at changing, influencing, and managing stakeholders’ perceptions of a corporate irresponsibility event. This will entail attempts to mitigate the perceived harm caused by the event, divert attention away from the event, and distort the attribution of blame. Such attempts will be more successful if the perceived harm and level of attention are initially low and blame is not clearly attributed.

Forgetting work can manipulate stakeholders’ perceptions of how harmful an event is, and, as such, it has an influence on the salience of the collective memory of the event in the future. For example, in $\mathsf { 2 0 1 3 ~ \mathsf { a } }$ government investigation revealed that many products being sold as beef in U.K. supermarkets actually contained horse meat from Romania. Immediately following the scandal, one of the largest grocery firms involved took out a one-page newspaper advertisement (in most daily newspapers) stating that this was a supply chain breach and that the consumption of horse meat posed no health risk for consumers. The question of deception was shifted to one of potential physical harm, with the majority of medical experts correctly stating that eating horse meat did not constitute a health risk for consumers.

Forgetting work can also involve manipulating the attention devoted to a corporate irresponsibility event. For instance, a firm and its affiliates might manipulate narratives targeted at different stakeholders through the media (Desai, 2014b). Such a strategy is facilitated by the fact that media attention is frequently short-lived (Fine, 2012; Hilgartner & Bosk, 1988; Kleinnijenhuis et al., 2015). Forgetting work can aim to change the tenor of news reporting (e.g., Fine, 2012), diverting attention to another issue (e.g., Zavyalova et al., 2012), diluting negative perceptions by emphasizing generic prosocial behavior (e.g., McDonnell & King, 2013), or presenting the firm in a more favorable light (e.g., Desai, 2014a,b; Pfarrer et al., 2008). For example, following an ecological disaster resulting from operations at the Talvivaara nickel mine in Finland, majority owner and CEO Pekka Perä stated that because of the focus on environmental issues in news coverage, the public had ignored the jobs and economic growth the mine had generated in the region (Virta, 2012).

The manipulation of narratives can also occur inside the firm (Desai, 2014b). Top-down communication from management about the “official” framing of an event can influence employees’ knowledge of it (Crossan et al., 1999; Desai, $2 0 1 4 \alpha ;$ March & Olsen, 1975). These official narratives are frequently translated into organizational memory and corporate history (Levitt & March 1988; Rowlinson et al., 2014; Schrempf-Stirling et al., 2016). Moreover, the narratives that appear immediately after an event can obscure some aspects of the event internally (Hedberg, 198l), with employees sometimes knowing less than external stakeholders (Argote, 2012).

Forgetting work can also manipulate the way blame is attributed for a particular corporate irresponsibility event. When blame is attributed to a firm, the firm can react by either accepting or denying responsibility. Denial is the most likely response (Zadek, 2004). Firms may also try to shift responsibility for the failure to other actors, such as subcontractors. But firms can also accept responsibility and address issues through either substantive action (King, 2008; Pfarrer et al., 2008) or symbolic action (MacLean & Behnam, 2010). Firms might apologize following a scandal, ask for forgiveness, and undertake substantive changes to their controversial practices (Pfarrer et al., 2008). Substantive changes can also be forced on them by regulators. Amnesty granted by a regulator and asking for forgiveness both increase the likelihood of long-term collective forgetting (Olick, 2007; Ricoeur, 2004). Firms can also accept responsibility but then engage only in symbolic or token gestures, making a surfacelevel change (that signals compliance) while leaving actual business practices unaltered (MacLean & Behnam, 2010; Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Oliver, 1991). For instance, following the financial scandals around predatory lending in the wake of the 2008 crisis, many organizations adopted ethics training programs but openly argued that high-risk credit was an industry-level problem rather than a specific organizational concern (Admati & Hellwig, 2013). By undertaking ceremonial rather than substantial changes in this manner, firms both accept and deflect blame, with the hope that forgiveness and ultimately forgetting may ensue (Ricoeur, 2004).

Silencing: Forgetting Work on the Stakeholder Mnemonic Community

In the longer term, forgetting work can also involve silencing members of a mnemonic community. This can have a significant influence on collective forgetting, because the memory of a past corporate irresponsibility event has to be sustained by someone (Brockmeier, 2002; Fine, 2012). Silencing members of a mnemonic community disconnects them from the past event and from each other, delegitimizes rememberers’ narratives as unworthy of being heard, and ultimately downplays their version of the past event. Silencing may be conducted at different points in time, since rememberers can be vocal at different moments. Silencing will thus be more successful if rememberers are less coordinated in their remembering work and unable to express their claims meaningfully.

In some cases actors might attempt to silence remembers by carefully monitoring their activities.

Nestlé, for example, hired a private security firm to infiltrate and spy on activists involved in a vocal NGO called Attac. Its aim was to prevent the group from divulging compromising information on Nestlé’s trade union policies (Crevoisier & Sansonnens, 2012).

Silencing may also function by co-opting certain rememberers within a mnemonic community and using their point of view to alter the narrative around the event. Co-optation is $\ " \alpha$ defensive mechanism" that integrates the narratives of oppositional groups “as a means of averting threats to [the organization’s] stability or existence” (Selznick, 1948: 34). This can be particularly effective when activist groups with strong public profiles are co-opted. To gain ground on a targeted firm, activist groups must often make concessions or become closer to the firm and so become less vocal or radical over time as a result (Jaffee, 2012; Trumpy, 2008; Zald, 2000). Such α reconfiguration of rememberers’ narratives further disconnects them from the event and ultimately erodes their remembering work (Trumpy, 2008).

Obviously, the media play an important role in facilitating the collective remembering of corporate irresponsibility events (Pfarrer et al., 2008). Silencing work can thus be directed at the media, which can be treated as a specific type of rememberer. Indeed, firms invest a great deal in controlling their media communications and how they are represented in the public realm (Desai, 2014a,b; Zavyalova et al., 2012). We have argued that forgetting work can manipulate short-term media attention, but long-term forgetting work can also focus on silencing the media. In his study of a large but long unknown U.S. oil spill in San Luis Obispo, Beamish (2000) reported that site managers repeatedly lied (i.e., stated that there was no spill) to the media to prevent the release of potentially damaging news stories.

Silencing may also be aimed at internal stakeholders. Organizational decision makers can repeat official narratives about a past event over time to prevent employees with “deviant memories” from speaking up (Levitt & March, 1988: 327; March & Olsen, 1975). Indeed, the memories of a lone employee are unlikely to influence collective memory (Argote, McEvily, & Reagans, 2003), especially when this employee perceives his or her viewpoint as that of a minority and, thus, fears exclusion (Bowen & Blackmon, 2003; Zerubavel, 2006). Barriers to whistle-blowing provide an apposite example of how employees are silenced in this manner. Potential whistle-blowers face immense obstacles to “going public” with their concerns. These obstacles include organizational culture and structure (Beamish, 2000; Morrison & Milliken, 2003), as well as the threat of direct intimidation from other members of the organization, often including top management (Miethe & Rothschild, 1994; Warren, 2007). Such barriers are reinforced by the official story of past events that has become embedded in the organization over time. In the case of the San Luis Obispo oil spill, employees remained silent about the spill for nearly forty years, not only because they feared punishment but also because the organization’s culture implicitly rendered the topic taboo (Beamish, 2000).

Undermining: Forgetting Work on Collective Mnemonic Traces

Forgetting work may also undermine collective memory by targeting the mnemonic traces of corporate irresponsibility events (Conway, 2003). Actors can undermine collective mnemonic traces in many ways: by destroying them, preventing access to them, distorting their meanings and associated beliefs, or even fabricating alternative traces that promote a different version of the past event (Booth et al., 2007; Ricoeur, 2004). It is easier to do this if mnemonic traces are few, weak, scattered, or even contradictory (Fine, 200l; Nora, 1989; Ricoeur, 2004).

Firms may destroy collective mnemonic traces, particularly those that are instantiated in a material artifact. This “structural amnesia” (Assmann, $1 9 9 5 \mathrm { \alpha } )$ is obvious when a firm destroys written mnemonic traces of a past corporate irresponsibility event, such as records and archives. This is what happened at HealthSouth (our opening example), where visible references to the disgraced CEO were erased from official documents and architecture. In a related example, monuments erected near Australian steel works to commemorate workers killed in industrial accidents were removed by the company during “redevelopment” (Ryan & Wray-Bliss, 2012).

Undermining forgetting work can also be conducted by inventing new, alternative traces. For example, the tobacco industry is known to have fabricated scientific evidence and reports “proving” that smoking tobacco is harmless (Palazzo & Mena, 2009). Nonmaterial mnemonic traces are fabricated by creating alternative narratives. Greenwashing, typically, is an attempt to undermine and reconfigure the beliefs related to α firm’s environmental behavior (Delmas & Cuerel Burbano, 20ll). Bansal and Clelland (2004) found that firms with low environmental legitimacy can nevertheless preserve their longterm reputation by repeatedly communicating about the natural environment and expressing their commitment to sustainable environmental practices, even when this commitment does not exist.

Yet another way that forgetting work can undermine collective mnemonic traces is by preventing a mnemonic community from accessing them. For example, a firm may divest from a region so that there is no longer a symbolically charged target to animate collective memory, or it may restructure the organization to “outsource” blame to a subsidiary (Pfarrer et al., 2008). This is exemplified in the case of Anadarko, a petroleum firm that recently “gifted” abandoned, contaminated sites to a subsidiary, Kerr-McGee. The mnemonic traces that might have aided collective recollection literally disappeared. Moreover, Kerr-Mcgee was restructured and sold its environmental debt to another company that, in the meantime, filed for bankruptcy (Cappiello & Tucker, 2014).

Forgetting work may also distort mnemonic traces by changing the norms and beliefs associated with them. This type of forgetting work deploys new mnemonic traces to tell an official story that aims to overshadow other ways of portraying the event (Crossan et al., 1999; Levitt & March, 1988). As a result, stakeholders who have profound and often disturbing memories of an event can find their memories being written out, marginalized, or excluded from the official narrative (Conway, 2003). For example, indigenous people in Australia who were violently displaced by the expansion of agricultural and mining industries argue that their suffering was actively obscured by official narratives of progress, modernization, and civilization. As a result, defining indigenous experiences and beliefs associated with their ancestral lands were undermined (Manne, 200l), aiding the overall dispossession process.

The same process applies to the deviant memories that employees may hold. The induction of new employees can significantly decrease the importance of disturbing mnemonic traces in the workforce by socializing them with values and beliefs (March, 199l) that omit more controversial elements of the past (Zerubavel, 1996). For example, Rowlinson (2002) described how Cadbury tells its own corporate history in the context of the Cadbury World museum and the booklet “The Cadbury Story.” In both, any uncomfortable connections to the slave labor used to produce cocoa in the past are absent.

Reconfiguration of Collective Memory and Consequences of Collective Forgetting

Forgetting work ultimately reconfigures the collective memory of a past event. Forgetting work aids reconfiguration because it reframes the past event in such a manner that it becomes more susceptible to recall failure. In the context of corporate irresponsibility, this is why much forgetting work is aimed at creating an alternative version of a past event that distances the firm from its responsibility for that event (e.g., Fine, 200l). In particular, silencing those who support an account of the event in which the firm is responsible enables the formulation of an alternative version of the past (Fine, 20l2). Alternative versions of the past often selectively evoke the past or even claim that certain past events are irrelevant to present matters (Assmann, 1995a). Moreover, when a past corporate irresponsibility event becomes irrelevant to the present, it no longer has any sort of impact on present practices or beliefs and will cease to serve as a template for similar actions in the future (Fine, 2012). Ultimately, we propose that this will lead to the absence of an institutionalized collective memory of the event, which equates to collective forgetting (Assmann, 1995a; Brockmeier, 2002; Fine, 2012).

With the collective forgetting of past instances of corporate irresponsibility, firms are able to maintain their organizational identity through denial or rationalization (Brown & Starkey, 2000; Gabriel, 1999; Pearson & Clair, 1998). The forgetting or remembering of specific events related to the focal firm by stakeholders has a strong influence on how the identity of the firm is perceived (Scott & Lane, 2000). Because “disasters call into question the social legitimacy and continued societal sanctioning of hazardous organizations, industries, and technologies” (Levitt & March, 1988: 324), forgetting also serves to legitimate the firm in its environment and to stabilize relationships with stakeholders, thereby ensuring its survival (Connerton, 2008; Erdelyi, 1990; Olick, 2007; Ricoeur, 2004). As such, collective forgetting has a number of positive consequences for the firm and the mnemonic community.

However, collective forgetting has negative consequences as well, the greatest of these being the failure to learn from past mistakes (e.g., Brunsson, 2009; Cannon & Edmondson, 2005; Madsen, 2009). For example, research on the mining industry suggests that, on average, firms tend to learn from disasters to some extent, but such learning diminishes over time as these events are forgotten (Madsen, 2009). While knowledge acquired through failure depreciates more slowly than knowledge from success (Madsen & Desai, 2010), we suggest that instrumental forgetting work may mitigate this process. As a result, fundamental lessons that may be learned from organizational failure remain untapped, and similar failures are likely to happen again (Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 201l). Furthermore, firms are less likely to learn from others’ mistakes if this occurs (Madsen, 2009). This is illustrated by the recent history of the Bangladeshi garment industry. Several incidents that threatened the lives of factory workers, including factory collapses in 2005, 2006, and 2010 and a lethal factory fire in 2012, were actively forgotten by management. Tragically, these events were followed by the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013 that claimed thousands of lives (Human Rights Watch, 2013), an event that is now much more salient in collective memory compared to previous similar incidents.

We also argue that as an event is forgotten, stakeholder pressure on the firm will weaken, which, in turn, will prompt members of the organization to increasingly forget lessons from the past. Thus, even if some routines have been put in place following an irresponsibility event, the firm will eventually relax the observance of those routines as a result of gradual forgetting (Madsen, 2009). The result is that it will become more likely the event will occur again (Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 2011).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this article we have developed a conceptual model to explain how some corporate irresponsibility events are forgotten despite their traumatic nature. Drawing on social and organizational memory studies, we have proposed that a corporate irresponsibility event can form a stakeholder mnemonic community comprising different actors who are bound together by a particular memory of that event. This community generates and draws on mnemonic traces as it seeks to keep that collective memory relevant. We have focused on how forgetting work can impede such attempts. Forgetting work can, in the short term, manipulate the immediate reactions to the event and, in the longer term, silence members of the mnemonic community and undermine collective mnemonic traces. While other forces might also lead to collective forgetting, we have suggested that forgetting work can facilitate the reconfiguration of collective memory and the collective forgetting of a corporate irresponsibility event. Several moderating effects will influence whether forgetting work is successful or not. The model is also subject to a number of limitations that may guide future research and contributions in this area.

Moderating Effects

It is reasonable to assume that there will be cases in which attempts to encourage collective forgetting do not succeed, or at least are not as effective as expected. One way to identify the most salient boundary conditions of the forgetting work modeled in this article is to examine moderating effects that might make forgetting work more or less likely to be effective. We approach the issue in this manner because we do not expect one type of forgetting work to be more effective than another in general. Although forgetting work can be conducted in singular instances (e.g., only at the outset of the event), we assume that it is most effective when carried out over time, in response to shifting and contingent conditions. Moreover, we have demonstrated how firms can manipulate the initial conditions of corporate irresponsibility events—notably, by denying or accepting responsibility. While the choice of such short-term responses is likely to shape the longerterm collective memory process, this does not prevent firms and other actors interested in forgetting from undertaking forgetting work concurrently or at later points in time. More specifically, we identify five moderating effects that may influence the effectiveness of forgetting work.

First, the initial conditions of corporate irresponsibility events (the degree of harm, the level of attention attracted, and the attribution of blame) will likely determine the amount of manipulating forgetting work required to successfully bring about the collective forgetting of an event. When the levels of harm and attention around an event of corporate irresponsibility are high and when an organization is unambiguously blamed for the event, forgetting work is likely to be less successful. This is because the event will be inherently more memorable, given its emotional resonance (Schacter, 1995, 2002; Schudson, 1995). In such cases remembrance of the event may persist despite the forgetting work undertaken.

Second, power must invariably play a role in determining whether actors engaged in forgetting work are able to effectively silence stakeholders and impede the formation of a robust mnemonic community. The level of power held by members of a mnemonic community will influence their capacity to perform authoritative remembering work. When rememberers have the power to coordinate and engage in organized mnemonic action, silencing them will be more difficult and less likely to lead to rapid collective forgetting (Armstrong & Crage, 2006; Fine, 2012). The same is true when rememberers are less accommodating to a firm, which will reduce the likelihood that their collective narrative will be co-opted. The collective remembering or forgetting of a past event will therefore hinge in large part on the mnemonic struggle that ensues and on the power of the actors involved.

Third, while undermining mnemonic traces at different points in time can hasten collective forgetting, this will depend on the number, substance, and cohesion of these traces. When collective mnemonic traces are numerous and easily accessible to stakeholders, forgetting work is less likely to facilitate rapid collective forgetting, because stakeholders can draw on these traces more easily to collectively remember (Fine, 200l; Nora, 1989; Ricoeur, 2004). When mnemonic traces exist but are contradictory or dispersed, firms involved in a corporate irresponsibility event can weave alternative narratives more easily (Spillman, 1998). Forgetting work is likely to be more successful in such cases. Efforts to undermine collective memory will also be affected by the intensity of the emotions attached to mnemonic traces. If traces are institutionalized and taken for granted (i.e., not marginal) in the mnemonic community, forgetting work will probably be less successful in hastening the process of collective forgetting (Fine, 2012).

Fourth, we suggest that the speed with which a firm assumes full responsibility for an event and asks for forgiveness from stakeholders is likely to facilitate collective forgetting, especially if the firm undertakes substantive changes to prevent the recurrence of similar events (Ricoeur, 2004). However, while a firm may ask for forgiveness from the outset (immediately following an event), it may still engage in forgetting work at the same time or later on. In some cases a firm might accept responsibility but still seek to silence some stakeholders, as has occurred among corporations involved in the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil spill. Therefore, we propose that forgetting work will be more effective and will lead to collective forgetting more rapidly when all three types of work are conducted over time and when responsibility is assumed rather than denied or only admitted long after the event.

And fifth, if the event is singular and unique in α specific organizational field-rendering it a stand-alone incident—then we suggest that forgetting work will be more difficult to accomplish than if the event is merely one of many similar events. This is because an event grouping that overpopulates an industry or sector will tend to dilute the attention that may have otherwise been attributed to one particular firm (Barnett, 2006; Desai, 20ll). Forgetting work can be expedited if the event is deemed an “industry problem,” rather than an individual organization one.

Limitations and Future Research

Our argument inevitably brings with it a number of limitations and unaddressed issues. These may inform future research on this topic. First, while we have built on social and organizational memory studies, we have not fully explored the impact of collective forgetting on internal organizational processes of memory and forgetting. As we have noted, employees may play a more or less active role in forgetting, depending on the nature of the corporate irresponsibility event. While we have emphasized the role of employees in our model of collective forgetting, we believe more research is required to understand the precise interactions between memory at the mnemonic community level and memory at the organizational level. For example, how can external and internal stakeholders interact more meaningfully in order to embed knowledge from past transgressions in a firm’s routines?

Second, more research is required to understand how the different types of forgetting work we have identified interact in concrete organizational settings. For example, we have assumed that each form of forgetting work reinforces the others in a processual manner. However, more attention could be devoted to exploring precisely how different forms of forgetting work impede or potentially reinforce one another. Special attention might be given to how the process of forgetting interacts with the dynamics of remembering. Examining the interplay between these forms of remembering and forgetting work more closely is likely to yield insights into the process of reconfiguring collective memory.

A third limitation and avenue for future research involves the role of forgiveness in collective forgetting. We usually assume that repentance leads to forgiveness, which will, in turn, wash away past transgressions and help us forget and move on (Ricoeur, 2004). As we have mentioned, forgiveness-seeking behavior does not necessarily prevent actors from undertaking forgetting work. But what exactly are the interactional dynamics between the request for forgiveness and the subsequent deployment of the different types of forgetting work? Moreover, the link between forgiveness and the memories of past transgressions (especially in the long term) is still conceptually tenuous in our argument. If forgiveness is granted, for example, is the corporate irresponsibility event forgotten, or does it simply lose its harsher negative connotations?

Our model risks imputing an unrealistically rational agent as the driver of forgetting work, which is the fourth limitation that might be further explored. To what extent is forgetting work by firms, managers, or other actors intentional and coordinated? The question has a number of interesting implications, especially in relation to business ethics. We have acknowledged that collective forgetting has clear benefits for the focal organization and sometimes for other stakeholders. But it can also yield negative outcomes for society in general, especially in terms of repeated mistakes and harm. Are forgetting workers cognizant of this ethical component when engaging in instrumental forgetting work? What would that imply for how we think about corporate responsibility and the role of firms in society? If forgetting work is the norm rather than the exception, we suggest an exploration of how more authentic collective memories might be supported, because, as Schacter vividly puts it, “a memory system that consistently produced seriously distorted outputs would wreak havoc with our very existence” (1995: 2).

Contributions

In this article we have sought to extend a number of existing debates in the study of corporate responsibility, as well as the study of memory in organization and management studies. First, we have developed the existing literature on reactions to corporate irresponsibility (e.g., Barnett, 2014; Hendry, 2005). Much of this research tends to concentrate on the short-term processes of audience evaluation, attention, and sensemaking of harmful events, as well as the politics of blame attribution (Lange & Washburn, 2012) and forgiveness (Pfarrer et al., 2008). By focusing on issues of (collective) memory, our argument highlights how an instance of corporate irresponsibility can have an impact that extends far beyond the audience’s immediate evaluation of events. And this longerterm impact is constructed and reconstructed in an ongoing manner by different actors (Fine, 2001). Thus, a complete understanding of how stakeholders evaluate corporate irresponsibility needs to incorporate the long-term development of mnemonic processes and the social forces that can thwart and undermine how we remember a traumatic event.

The second debate we have contributed to concerns memory in organization and management studies. Several areas of research have identified how memory in organizations becomes a collective achievement that is reached through organizational routines (Arthur & Huntley, 2005; Levitt & March, 1988; Walsh & Ungson, 1991) and the articulation and circulation of narratives, stories, and experiences (Anteby & Molnár, 2012; Booth et al., 2007), and how it can ultimately serve to establish a competitive advantage (Argote, 2012; Foster et al., 201l; Suddaby et al., 2010). However, we note that memory is not only reducible to organizational-level or competitive dynamics within a population of firms (e.g., Madsen, 2009) but can also pertain to and be shaped by mnemonic communities of stakeholders who operate at a supraorganizational level with little interest in the firm’s competitiveness. Even if a firm and its competitors may have forgotten a particular past event, the collective memory of that event may still be relevant to actors outside these firms.

As well as articulating a broader conceptualization of memory, we explore another aspect of the mnemonic process: forgetting. Many contemporary organizations appear to go to great lengths to guarantee that lessons learned from the past are forgotten and eliminated from organizational memory (Alvesson, 2013; Brunsson, 2009; Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984). We believe this forgetting work is a central reason why particular memories come to be excluded from the shared narratives that stakeholders have of an organization. We suggest that forgetting does not only imply the positive consequences that existing research has tended to emphasize (e.g., de Holan & Phillips, 2004; de Holan, Phillips, & Lawrence, 2004). It can also have more negative social implications. In particular, it can facilitate an inability to learn from past mistakes, encouraging the repetition of questionable and even harmful courses of action (Brunsson, 2009; Easterby-Smith & Lyles, 20l1). Forgetting might even serve as a sort of resource for perpetuating questionable behavior in a systematic fashion. In this respect, we hope this article inspires future research into the wider implications of how major instances of corporate irresponsibility are remembered and forgotten.

REFERENCES

Admati, A., & Hellwig, M. 2013. The bankers’ new clothes: What’s wrong with banking and what to do about it. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Aksu, E. Ü. 2009. Global collective memory: Conceptual difficulties of an appealing idea. Global Society, 23: 317332.

Alvesson, M. 2013. The triumph of emptiness: Consumption, higher education, and work organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anteby, M., & Molnár, V. 2012. Collective memory meets organizational identity: Remembering to forget in a firm’s rhetorical history. Academy of Management Journal, 55: 515-540.

Argote, L. 2012. Organizational learning: Creating, retaining and transferring knowledge. New York: Springer.

Argote, L., Beckman, S. L., & Epple, D. 1990. The persistence and transfer of learning in industrial settings. Management Science, 36: 140154.

Argote, L., McEvily, B., & Reagans, R. 2003. Managing knowledge in organizations: An integrative framework and review of emerging themes. Management Science, 49: 571582.

Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E. 2011. Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organization Science, 22: 11231137.

Armstrong, E. A., & Crage, S. M. 2006. Movements and memory: The making of the Stonewall myth. American Sociological Review, 71: 724751.

Arthur, J. B., & Huntley, C. L. 2005. Ramping up the organizational learning curve: Assessing the impact of deliberate learning on organizational performance under gainsharing. Academy of Management Journal, 48: 1159-1170.

Assmann, J. 1995a. Ancient Egyptian antijudaism: A case of distorted memory. In D. L. Schacter (Ed.), Memory distortion: How minds, brains, and societies reconstruct the past: 365385. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Assmann, J. 1995b. Collective memory and cultural identity. New German Critique, 65: 125-133.

Bansal, P., & Clelland, I. 2004. Talking trash: Legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Academy of Management Journal, 47: 93103.

Barkemeyer, R., Holt, D., Figge, F., & Napolitano, G. 2010. A longitudinal and contextual analysis of media representation of business ethics. European Business Review, 22: 377396.

Barnett, M. L. 2006. Finding a working balance between competitive and communal strategies. Journal of Management Studies, 43: 17531773.

Barnett, M. L. 2014. Why stakeholders ignore firm misconduct: A cognitive view. Journal of Management, 40: 676702.

Beamish, T. D. 2000. Accumulating trouble: Complex organization, a culture of silence, and a secret spill. Social Problems, 47: 473498.

Blaschke, S., & Schoeneborn, D. 2006. The forgotten function of forgetting: Revisiting exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Soziale Systeme, 12: 99-119.

Bonardi, J.-P., & Keim, G. D. 2005. Corporate political strategies for widely salient issues. Academy of Management Review, 30: 555576.

Booth, C., Clark, P., Delahaye, A., Procter, S., & Rowlinson, M. 2007. Accounting for the dark side of corporate history: Organizational culture perspectives and the Bertelsmann case. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 18: 625644.

Booth, C., & Rowlinson, M. 2006. Management and organizational history: Prospects. Management & Organizational History, 1: 530.

Bowen, F., & Blackmon, K. 2003. Spirals of silence: The dynamic effects of diversity on organizational voice. Journal of Management Studies, 40: 13931417.

Brockmeier, J. 2002. Remembering and forgetting: Narrative as cultural memory. Culture & Psychology, 8: 1543.

Brockmeier, J. 2010. After the archive: Remapping memory. Culture & Psychology, 16: 535.

Brown, A. D., & Starkey, K. 2000. Organizational identity and learning: A psychodynamic perspective. Academy of Management Review, 25: 102120.

Brunsson, N. 2009. Reform as routine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bundy, J., Shropshire, C., & Buchholtz, A. K. 2013. Strategic cognition and issue salience: Toward an explanation of

firm responsiveness to stakeholder concerns. Academy of Management Review, 38: 352376.

Campbell, J. L. 2007. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32: 946967.

Cannon, M. D., & Edmondson, A. C. 2005. Failing to learn and learning to fail (intelligently): How great organizations put failure to work to innovate and improve. Long Range Planning, 38: 299319.

Cappiello, D., & Tucker, E. 2014. US reaches $$ 5.15$ billion environmental settlement. AP: The Big Story, April 4: http:// bigstory.ap.org/article/us-reaches-515-billion-environmentalsettlement.

Casey, A. J., & Olivera, F. 20ll. Reflections on organizational memory and forgetting. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20: 305310.

Connerton, P. 2008. Seven types of forgetting. Memory Studies, 1: 5971.

Conway, B. 2003. Active remembering, selective forgetting, and collective identity: The case of Bloody Sunday. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 3: 305323.

Cooke, B. 2003. The denial of slavery in management studies. Journal of Management Studies, 40: 1895-1918.

Coraiola, D. M., Foster, W. M., & Suddaby, R. 2015. Varieties of history in organization studies. In P. G. McLaren, A. J. Mills, & T. G. Weatherbee (Eds.), The Routledge companion to management and organizational history: 206221. Oxford & New York: Routledge.

Crane, A. 2013. Modern slavery as a management practice: Exploring the conditions and capabilities for human exploitation. Academy of Management Review, 38: 4969.

Crevoisier, A., & Sansonnens, Y. 2012. Quand Nestlé faisait espionner Attac [When Nestlé had Attac spied on]. Le Monde Diplomatique, January 27: https://www.mondediplomatique.fr/carnet/2012-01-27-Nestle-Attac.

Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., & White, R. E. 1999. An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review, 24: 522537.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. 1963. A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Darr, E. D., Argote, L., & Epple, D. 1995. The acquisition, transfer, and depreciation of knowledge in service organizations: Productivity in franchises. Management Science, 41: 17501762.

de Holan, P. M. 2011. Agency in voluntary organizational forgetting. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20: 317322.

de Holan, P. M., & Phillips, N. 2004. Remembrance of things past? The dynamics of organizational forgetting. Management Science, 50: 16031613.

deHolan, P. M. Phillps, N., & Lawrence, T. B. 2004. Maig organizational forgetting. MIT Sloan Management Review, 45(2): 4551.

Delmas, M. A., & Cuerel Burbano, V. 2011. The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1): 6487.

Desai, V. M. 20ll. Mass media and massive failures: Determining organizational efforts to defend field legitimacy following crises. Academy of Management Journal, 54: 263278.

Desai, V. M. 2014α. Does disclosure matter? Integrating organizational learning and impression management theories to examine the impact of public disclosure following failures. Strategic Organization, 12: 85108.

Desai, V. M. 2014b. The impact of media information on issue salience following other organizations’ failures. Journal of Management, 40: 893918.

Easterby-Smith, M., & Lyles, M. A. 201l. In praise of organizational forgetting. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20: 311-316.

Elsbach, K. D., Sutton, R. I., & Principe, K. E. 1998. Averting expected challenges through anticipatory impression management: A study of hospital billing. Organization Science, 9: 6886.

Erdelyi, M. H. 1990. Repression, reconstruction, and defense: History and integration of the psychoanalytic and experimental frameworks. In J. L. Singer (Ed.), Repression and dissociation: Implications for personality theory, psychopathology, and health: 1-3l. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fernandez, V., & Sune, A. 2009. Organizational forgetting and its causes: An empirical research. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 22: 620634.

Fig, D. 2005. Manufacturing amnesia: Corporate social responsibility in South Africa. International Affairs, 81: 599617.

Fine, G. A. 1996. Reputational entrepreneurs and the memory of incompetence: Melting supporters, partisan warriors, and images of President Harding. American Journal of Sociology, 101: 11591193.

Fine, G. A. 200l. Difficult reputations: Collective memories of the evil, inept, and controversial. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fine, G. A. 2012. Sticky reputations: The politics of collective memory in midcentury America. New York: Routledge.

Fiol, C. M., & Lyles, M. A. 1985. Organizational learning. Academy of Management Review, 10: 803813.

Fleming, P., & Jones, M. T. 2013. The end of corporate social responsibility: Crisis and critique. London: Sage.

Foster, W. M., Suddaby, R., Minkus, A., & Wiebe, E. 201l. History as social memory assets: The example of Tim Hortons. Management & Organizational History, 6: 101-120.

Gabriel, Y. 1999. Organizations in depth: The psychoanalysis of organizations. London: Sage.

Gephart, R. P. 1993. The textual approach: Risk and blame in disaster sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 36: 14651514.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. 2009. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30: 425445.

Goodman, S. C. 2003. Rebranding HealthSouth? AL.com, April 13: http://www.al.com/specialreport/birminghamnews/ index.ssf?healthsouth/healthsouth61.html.

Greve, H. R. 2005. Interorganizational learning and heterogeneous social structure. Organization Studies, 26: 1025-1047.

Gross, D. 2000. Lost time: On remembering and forgetting in late modern culture. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Halbwachs, M. 1992. On collective memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Halbwachs, M. 1994. (First published in 1925.) Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire [The social frameworks of memory]. Paris: Albin Michel.

Halbwachs, M. 1997. (First published in 1950.) Lα mémoire collective [On collective memory]. Paris: Albin Michel.

Hansen-Glucklich, J. 2014. Holocaust memory reframed: Museums and the challenges of representation. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Hedberg, B. 1981. How organizations learn and unlearn. In P. C. Nystrom & W. H. Starbuck (Eds.), Handbook of organizational design: 3-27. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hendry, J. R. 2005. Stakeholder influence strategies: An empirical exploration. Journal of Business Ethics, 61: 7999.

Hilgartner, S., & Bosk, C. L. 1988. The rise and fall of social problems: A public arenas model. American Journal of Sociology, 94: 5378.

Hirst, W., & Manier, D. 2008. Towards a psychology of collective memory. Memory, 16: 183200.

Hobsbawm, E., & Ranger, T. 1983. The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoffman, A. J. 1999. Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the U.S. chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, 42: 351371.

Hoffman, A. J., & Jennings, P. D. 20ll. The BP oil spill as a cultural anomaly? Institutional context, conflict, and change. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20: 100-112.

Hoffman, A. J., & Ocasio, W. 2001. Not all events are attended equally: Toward a middle-range theory of industry attention to external events. Organization Science, 12: 414434.

Holt, D., & Barkemeyer, R. 2012. Media coverage of sustainable development issues-Attention cycles or punctuated equilibrium? Sustainable Development, 20: 1-17.

Human Rights Watch. 2013. Bangladesh: Tragedy shows urgency of worker protections. hrw.org, April 25: http:// www.hrw.org/news/2013/04/25/bangladesh-tragedy-showsurgency-worker-protections.

Ingram, P., Yue, L. Q., & Rao, H. 2010. Trouble in store: Probes, protests, and store openings by Wal-Mart, 1998-2007. American Journal of Sociology, 116: 5392.

Jaffee, D. 2012. Weak coffee: Certification and co-optation in the fair trade movement. Social Problems, 59: 94116.

Javeline, D. 2003. The role of blame in collective action: Evidence from Russia. American Political Science Review, 97: 107121.

Kammen, M. 1995. Some patterns and meanings of memory distortion in American history. In D. L. Schacter (Ed.), Memory distortion: How minds, brains, and societies reconstruct the past: 33l-345. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

King, B. G. 2008. A political mediation model of corporate response to social movement activism. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53: 395421.

Kipping, M., & Üsdiken, B. 2014. History in organization and management theory: More than meets the eye. Academy of Management Annals, 8: 535588.

Kleinnijenhuis, J., Schultz, F., Utz, S., & Oegemα, D. 2015. The mediating role of the news in the BP oil spill crisis 2010: How US news is influenced by public relations and in turn influences public awareness, foreign news, and the share price. Communication Research, 42: 408428.

Lang, G. E., & Lang, K. 1988. Recognition and renown: The survival of artistic reputation. American Journal of Sociology, 94: 79109.

Lange, D., & Washburn, N. T. 2012. Understanding attributions of corporate social irresponsibility. Academy of Management Review, 37: 300326.

Levitt, B., & March, J. G. 1988. Organizational learning. Annual Review of Sociology, 14: 319340.

Lin-Hi, N., & Müller, K. 2013. The CSR bottom line: Preventing corporate social irresponsibility. Journal of Business Research, 66: 19281936.

MacLean, T. L., & Behnam, M. 2010. The dangers of decoupling: The relationship between compliance programs, legitimacy perceptions, and institutionalized misconduct. Academy of Management Journal, 53: 14991520.

Madsen, P. M. 2009. These lives will not be lost in vain: Organizational learning from disaster in U.S. coal mining. Organization Science, 20: 861875.

Madsen, P. M., & Desai, V. 2010. Failing to learn? The effects of failure and success on organizational learning in the global orbital launch vehicle industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53: 451476.

Manne, R. 2001. In denial: The stolen generations and the right. Melbourne: Black Inc.

March, J. G. 1991. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2: 7187.

March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. 1975. The uncertainty of the past: Organizational learning under ambiguity. European Journal of Political Research, 3: 147-171.